Original guest article by Michael Elwood and Tarik Abdallah

Recently, there’s been a lot in the news as to whether extremists like ISIS are being true to the message of the Quran or not.

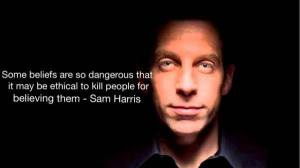

Some, like Rep. Keith Ellison and Prof. Rashid Khalidi claim that groups like ISIS take verses of the Quran out of context in order to justify their objectionable beliefs and practices (see: Islamic State group uses only half of a Quran verse to justify beheadings — see what’s in the other half). Others, like Sam Harris and Bill Maher, claim that so-called moderate Muslims either don’t know what their own scripture says (as incredible as that sounds!), or they’re simply lying about the “violent” and “hateful” contents of the Quran. We contend it’s extremists like ISIS, and critics of Islam like Harris and Maher, who are lying about the contents of the Quran. Below, we’ll give an overview of how they do this by taking verses out of context in order to make them appear to be advocating “violence” and “hate”.

First, we’d like to point out that taking verses out of context isn’t the only way that extremists try to justify violent and hateful interpretations of the Quran. There are two other ways that this is often accomplished. One way is to play on verses that are allegorical, or that can have more than one meaning, and try to tease a violent or hateful interpretation from them. The Quran itself mentions this:

“He sent down to you this scripture, containing straightforward verses – which constitute the essence of the scripture – as well as multiple-meaning or allegorical verses. Those who harbor doubts in their hearts will pursue the multiple-meaning verses to create confusion, and to extricate a certain meaning. None knows the true meaning thereof except GOD and those well founded in knowledge. They say, “We believe in this – all of it comes from our Lord.” Only those who possess intelligence will take heed” ~ Quran 3:7

In their footnote for 3:7, Prof. Edip Yuksel, Prof. Martha Schulte-Nafeh, et. al., point out that the verse about verses that can be interpreted in more than one way, can itself be interpreted in more than one way (See “Quran: A Reformist Translation”):

“The word [mutashabihat] can be confusing for a novice. Verse 39:23, for instance, uses mutashabihat for the entire Quran, referring to its overall similarity — in other words, its consistency. In a narrower sense, however, mutashabihat refers to all verses which can be understood in more than one way. The various meanings or implications require some special qualities from the person listening to or reading the Quran: an attentive mind, a positive attitude, contextual perspective, the patience necessary for research, and so forth.

“It is one of the intriguing features of the Quran that the verse about mutashabih verses of the Quran is itself mutashabih — that is, it has multiple meanings. The word in question, for instance, can mean ‘similar’, as we have seen; it can mean, ‘possessing multiple meanings’; it can also mean ‘allegorical’ (where one single, clearly identifiable element represents another single, clearly identifiable element).”

An example of a verse that can be interpreted in more than one way is 2:106. In this verse, some translate the word “ayah,” which means “miracle,” as “verse” in order to justify abrogating Quranic verses that are inconvenient for them (more on this later). An example of verses that are allegorical are the verses that describe heaven and hell, like 47:15. In this particular instance, the Quran actually tells us that the description is an allegory (mathalu):

“The allegory of Paradise [mathalu al-jannati] that is promised for the righteous is this: it has rivers of unpolluted water, and rivers of fresh milk, and rivers of wine – delicious for the drinkers – and rivers of strained honey. They have all kinds of fruits therein, and forgiveness from their Lord. (Are they better) or those who abide forever in the hellfire, and drink hellish water that tears up their intestines?” ~ Quran 47:15

In his book, “The End of Faith,” and on his website, Sam Harris often cites these verses as evidence of what he calls “religious hatred” and “otherwordliness” in the Quran (see Honesty: The Muslim World’s Scarcest Resource). There are a few problems with this, however.

First, as his fellow atheist Joshua Oxley points out, these verses use imagery to portray the torments of hell:

“The verses cited aren’t quite as scary as he makes them out to be. Many of them use violent imagery–fire, mostly–to convey the judgment that us unbelievers will experience at the hands of God. Not at the hands of men and women on earth. But at the Last Day. Why should this constitute a particular kind of Islamic violence. . . . Does that scare you? It doesn’t scare me. These passages put the power into Divine hands to judge and cast out, not human. I couldn’t care less, unless individuals start citing that verse in hopes of having my head. At that point, it’s not the ‘unified message’ of the text that is to blame, but an inconsistent interpretation by the religious believer. And those are two very, very different things.

“Harris, quite frankly, presents Scripture here as a fundamentalist would. It is a dry, topical understanding, devoid of historical or textual context, that makes proof-texting possible. There is no room for interpretation, for conversation, for nuance. No different schools of thought. It’s decided, ‘The text as a whole says X’. Islam becomes a robotic, artificial existence, and humankind mere automatons. And I feel like Harris should know better. When you have a bigger audience to speak to, you take on the responsibility of presenting yourself and others with as much integrity and honesty as possible. And this article just doesn’t measure up. . . .

“Please, anyone and everyone, don’t take Harris’ analysis as your own understanding of Islam. I have to say something. This atheist, who is not a Qur’anic scholar, but who was lucky enough to spend four year in undergrad studying Islam, is interested in the Muslim and secular communities engaging in dialogue over real issues. Poorly-reasoned critiques, more diatribe than discourse, will never get people to the table. And in a society with a profound ignorance of the nature of Islam, it’s even more dangerous to promulgate some of the worst misconceptions.

“Everyone deserves to be as generously understood as possible, and it’s about time the Muslim community got similar treatment from our secular circles. If I read a Muslim thinker picking any secular text apart in this kind of manner, I’d be equally miffed.” ~Joshua Oxley, When You Just Shouldn’t Say Anything: Sam Harris and the Qur’an

Second, Harris isn’t categorically against torment. He’s just against the torment of non-Muslims (or infidels as he likes to call them) in an afterlife he doesn’t believe in, by a God he doesn’t believe in. But as he has said in his book “The End of Faith,” and in a Huffington Post article aptly titled “In Defense of Torture,” he’s all for the torment of Muslims in this life.

It’s hard to understand how the torment of some non-Muslims in the afterlife constitutes “religious hatred,” but the torment of some Muslims in this life doesn’t constitute “secular hatred”.

Third, despite Harris’ subjective impression that the Quran is full of “otherworldliness,” the objective reality is quite different. The number of times the Arabic words for this life (dunya) and the afterlife (akhira) both occur in the Quran exactly 115 times (see “Quran: A Reformist Translation”). It reminds me of the Christian apologist Dave Miller who tried to demonstrate that the Quran, unlike the Bible, emphasizes hell more than heaven. He wrote:

“While the Bible certainly emphasizes the certainty and inevitability of eternal punishment, it places the subject in proper perspective and provides a divinely balanced treatment.” ~ David Miller, Hell and the Quran

But despite Miller’s subjective impression of the Quran placing an emphasis on hell, the objective reality is quite different. The Arabic words for heaven (jannah) and hell (jahannum) both occur in the Quran exactly 77 times (see “Interpreting the Qur’an: A Guide for the Uninitiated” by Clinton Bennett). If that’s not “balanced treatment,” what is? It should also be pointed out that Christian apologists claim that overall the Quran, unlike the Bible, is more violent (see Dark passages: Does the harsh language in the Koran explain Islamic violence? Don’t answer till you’ve taken a look inside the Bible, also see Danios’ article: What the Quran-bashers Don’t Want You To Know About The Bible).

Another way extremists and critics try to justify violent and hateful interpretations of the Quran is to just ignore or explain away “peaceful” and “loving” verses in the Quran. One of the ways they try to accomplish this is by claiming that all the “peaceful” and “loving” verses of the Quran have been conveniently abrogated. Verse 2:106, mentioned earlier, “critics” claim can be interpreted in more than one way through abrogation. Many also claim verse 9:5 abrogates all the other “peaceful” and “loving” verses. However, some scholars disagree:

“A popular argument against such a reading of the text is based on the claim that verses such as 22:39-40 and 2:190 have been abrogated by the so-called ‘verse of the sword,’ 9:5. Proponents of this argument generally cite the portion of the verse, which says, ‘then kill the polytheists wherever you find them,’ claiming that this abrogates any previous verses that seem to restrict fighting and killing non-Muslims. However, this argument is problematic for two very important reasons.

“First, as John Burton has clearly demonstrated, there is no agreement among Muslim scholars, past or present, on the nature of abrogation, or on the specifics of the abrogating and the abrogated.[16] More important to the present discussion, however, is the fact that a literal reading of 9:5, in the surrounding context demonstrates that its message is the same as that found throughout the Qur’an.” ~ Prof. Aisha Musa, Towards a Qur’anically-Based Articulation of the Concept of ‘Just War’

For a lengthier treatment of abrogation, see Dr. Israr Khan’s article Arguments for Abrogation in the Qur’an: A Critique. Also see the article Abrogation, the biggest lie against the Quran.