Original Guest article by Mehdi

This article is not intended to explain the differences between Islam and Judaism, nor is it an attempt to provide a comprehensive narrative of Jewish-Muslim relations globally. This article is based on personal impressions and an analysis of a common history that will analyze the relational dynamics between Jewish and Muslim communities where they have coexisted.

I began writing this article based on the impression that something has been broken, 13 centuries of positive coexistence between Muslims and Jews has been erased in half a century. A common history is on the verge of extinction; like a family quarrel leading to a gradual distancing, cousins moving apart, to the point that they have stopped being a family. We have become all too familiar to events such as the most recent instance of Israel “mowing the lawn in Gaza,” devastating and massacring countless innocents and in a tit for tat Israelis have also been killed (e.g. the kidnapping and murder of 3 Israeli teenagers last summer or the attack on a synagogue last November in Jerusalem).

This is the contemporary backdrop of a complicated and rich history and hence it is impossible to have a completely objective and comprehensive discussion. The main difficulty is not in addressing the different angles or perspectives, it is putting passions aside for a moment, and reflecting on what united Muslims and Jews. Therefore, readers of this article are kindly asked to indulge the author, whose objective is to tell a story, and remind people of how close Jews and Muslims have been throughout history, and the level of greatness of the civilization that they built together; it is the memory of these achievements that can provide a framework that would help fix the contemporary problems, and build something new.

Morocco and a few personal reflections

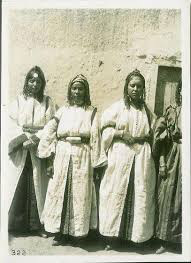

Before jumping into the historic perspective, I would like to write a few lines about my personal background. I grew up in Morocco, where Judaism has historically been very present (in fact long before Islam’s arrival in the 7th century, most historians estimate its existence to 2000 years). There are many reminders of Morocco’s rich Jewish history, from historical figures such as Al Kahina, Joseph Toledani, or more recently, Jewish Moroccans like: political activist Abraham Serfaty (anti-zionist Marxist militant, who spent many years in jail as a political prisoner), anti-Zionist militant Sion Assidon who is BDS’s main representative in Morocco, to a very different personality such as André Azoulay, on the other side of the political spectrum (businessman and king’s adviser, also in charge of relationships between Morocco and the Moroccan Jewish diaspora in the USA, Canada, France or Israel), writers such as the late Edmond Amran El Maleh, or the hugely popular humorist Gad El Maleh whose jokes are known by heart by most Moroccans. Jewish cuisine, humor, music are also part of Moroccan identity, for instance the Moroccan Andalusian classical music and its poetry often includes a clear Jewish dimension (as in this moving wedding song), several orchestras play this music in Israel after Moroccan Jews emigrated there. Even in some mosques in the south, stars of David can be seen as they were a form of recognition for the Jewish artisans who contributed to building those mosques. Sights like these are pretty common in Morocco:

Coin collectors in Morocco (as I have been) are also used to seeing Stars of David on coins that date back to the first half of the 20th century or before, since Jewish artisans of Essaouira produced coins for Moroccan currency.

Coin collectors in Morocco (as I have been) are also used to seeing Stars of David on coins that date back to the first half of the 20th century or before, since Jewish artisans of Essaouira produced coins for Moroccan currency.

To these historical reminders, I add personal memories and stories coming from my father and my grandmother who lived in Sefrou, a town that had a significant Jewish population. My grandmother, a very conservative and proud woman, very clear about her Muslim identity, never had a single negative word about Jews. She always cherished memories of her neighbors, getting angry with people who made any sort of anti-Jewish remarks. I always found it interesting to notice how my father and grandmother, both quite religious were immune from any anti-Jewish prejudice unlike other more “secularized” family members.

To these historical reminders, I add personal memories and stories coming from my father and my grandmother who lived in Sefrou, a town that had a significant Jewish population. My grandmother, a very conservative and proud woman, very clear about her Muslim identity, never had a single negative word about Jews. She always cherished memories of her neighbors, getting angry with people who made any sort of anti-Jewish remarks. I always found it interesting to notice how my father and grandmother, both quite religious were immune from any anti-Jewish prejudice unlike other more “secularized” family members.

My father was proud to tell me about my grandfather, a judge, who had great respect for Judaism, who once received a Muslim who wanted to marry a Jewish woman and wanted him to convince her to convert to Islam. My grandfather asked him a few religious questions (that the man answered poorly), and then told him: “I have enough on my plate trying to make people like you and in this town better people and Muslims! Why would I push this woman to abandon a religion she is probably very happy with? Leave this woman alone, marry her and do your best to become a better Muslim. Respect her faith, remember that Moussa PBUH is also a prophet of ours”.

My father and my late grandmother would usually tell me other positive stories about their life with their Jewish neighbors, and also with sadness, about their neighbors’ sudden and surprising departure. I will come back to this point later on, as there is a history behind it, but this recollection of events is essential, and is consistent with what many Moroccans remember from the 1950s and 1960s.

I was personally privileged to have this background and insight into Moroccan history; I was never attracted by any anti-Jewish sentiment thanks to the education I received and the positive image of Jews relayed by my family. I was able to differentiate, due to this education, between the policies carried out by the Israeli state in the name of Jews and what most ordinary Jews stand for. I went on to have many Jewish friends, I also recall many experiences traveling where I would meet (on an airplane, a hotel restaurant, or during a dinner with acquaintances) Israelis of Moroccan origin, and how they had a great smile when they found out I came from Morocco, leading to very friendly discussions involving humor, food, or just culture. This helped me grasp how history did impact people’s lives, creating a huge distance, but at the same time, how a lot of common background was still there making us close.

I was personally privileged to have this background and insight into Moroccan history; I was never attracted by any anti-Jewish sentiment thanks to the education I received and the positive image of Jews relayed by my family. I was able to differentiate, due to this education, between the policies carried out by the Israeli state in the name of Jews and what most ordinary Jews stand for. I went on to have many Jewish friends, I also recall many experiences traveling where I would meet (on an airplane, a hotel restaurant, or during a dinner with acquaintances) Israelis of Moroccan origin, and how they had a great smile when they found out I came from Morocco, leading to very friendly discussions involving humor, food, or just culture. This helped me grasp how history did impact people’s lives, creating a huge distance, but at the same time, how a lot of common background was still there making us close.

I also remember a funny anecdote that happened to a late uncle. He planned a business trip to India, and had his ticket booked by a third party who did not pay attention to the stops on the way. My uncle was on his way to India, enjoying his flight, and was stunned to hear the flight crew announce that the plane was about to land in Tel Aviv, at a time when Israeli-Arab wars and tensions were at their peak, he was mad and refused to leave the plane. The plane crew gave up on convincing him to leave the plane while it prepared for the rest of the trip. Staff was sent to clean the plane, my uncle still angry, sat alone waiting, when suddenly he heard a voice speaking in a typical Moroccan dialect, asking him, “Brother, why are you sitting here by yourself? Can I at least go get you some water or an orange juice?” Yes, members of the cleaning staff were Jews born in Morocco.

Growing up in Morocco in the 1980s, there were very few Jews left (at least compared to the 300,000 Moroccan Jews who lived in the country during the 1950s). The previously important community was now a small group of people, mostly living in Casablanca. In the little town in south east Morocco where I grew up, the only Jews were the charming tailor and his wife. At the same time that a new generation of Moroccans had few Jewish acquaintances, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was omnipresent on TV: Moroccans watched coverage of the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, the Sabra and Chatila massacres, the repression of the first Intifada, the expansion of settlements in the occupied territories, which distorted the image of the Jew for many young Moroccans. While their parents would identify Jews as their neighbors, their children would be tempted to think of them first as the Israeli soldier now repressing their Palestinian brothers. I would later realize that many Jews (not only Israelis) identified the Muslim as a potential terrorist, a mirroring of the distorted way in which Moroccans viewed Jews; it’s clear, distance and headlines creates fear and misunderstanding.

The official history in Morocco as told in the media and books, emphasizes the Muslim nature of the country and is evasive regarding its Jewish history. The official history is not aggressive or Antisemitic in any sense but it diminishes the important Jewish role in Morocco’s history, reducing it to a few anecdotes and personalities. We often discussed these questions in more depth at the end of history courses in high school with our teachers but they were brief mentions in our textbooks. While I acknowledge that my personal experience and the general context in Morocco was different from other Arab countries, something was missing. Recently, a new generation of historians and artists has dug into this poorly written history.

- A film by French-Moroccan director Kamal Hachkar about the history of Jewish Berbers from Tinghir who emigrated to Israel met some controversy but also a lot of success, winning a prize and drew large audiences, debates (a follow-up is upcoming, and is still being presented throughout Morocco with many people coming to watch it and debate).

- Jewish pilgrims still come to visit graves of Jewish saint figures such as the Toulal pilgrimage near Gourrama (south East) for instance, gathering sometimes thousands of visitors with growing media coverage.

- Several art festivals now regularly invite Israeli artists of Moroccan origins (though these are controversial in light of BDS).

- Many interfaith dialogue initiatives also take place, even involving important figures such as the Muslim conservative prime minister.

- Many historians now write and publish several works on Morocco’s Jewish history, whether about specific cities such as Tetuan, entire regions, or even when history magazine Zamane referred to Morocco as a “Jewish land”.

- In Israel, many Israelis of Moroccan origin try to rebuild bridges, including artists such as singer Neta Elkayam (who is the subject of the Jerusalem Tinghir movie), or jazz bass player Omer Avital who is deeply inspired by his parent’s Moroccan/Yemeni heritage and reflects that in his music.

- Many “Israeli Moroccans” keep visiting Morocco for different matters.

Other Arab countries also look towards their Jewish history with different backgrounds and perspectives, this interest in itself is a positive step and shows that Muslim-Jewish coexistence in MENA exists.

These initiatives do not change the fact that there are many problems, especially as the suffering of the Palestinians is as deep as ever, any long term improvement and prospect of coexistence will be accompanied by a just solution that addresses these sufferings (and not with a so-called peace process focused only on security measures, totally evading Palestinian people’s daily lives).

Nevertheless, these initiatives shed light on a rich common history that no longer is burning as bright as it used to but still deserves to be recounted.