This is part 5-ii of the Understanding Jihad Series. Please read my “disclaimer”, which explains my intentions behind writing this article: The Understanding Jihad Series: Is Islam More Likely Than Other Religions to Encourage Violence?

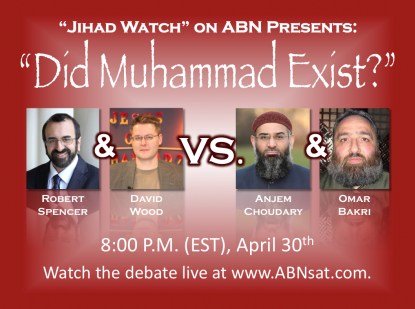

Throughout his book The Politically Incorrect Guide to Islam (and the Crusades), professional Islamophobe Robert Spencer misleads the reader by selectively comparing Muhammad to Jesus. Muhammad is portrayed as a “warrior prophet” and contrasted with the (supposedly) non-violent Jesus. Spencer argues on page four of his book that his “Muhammad vs. Jesus” comparisons are intended to “draw a distinction between the core principles that guide the faithful Muslim and Christian.” We are told that Islam’s militancy stems from its founder, as Christianity’s peacefulness traces back to its earliest figure. Although Robert Spencer is a fringe extremist, his sentiments are shared by many average Christians (and even non-Christians). To the average Westerner, Muhammad was a man of violence, whereas Jesus was the quintessential pacifist.

Prof. Philip Jenkins explored a similar mindset when it came to the Koran and the Bible. Jenkins explained (emphasis added):

Unconsciously, perhaps, many Christians consider Islam to be a kind of dark shadow of their own faith, with the ugly words of the Koran standing in absolute contrast to the scriptures they themselves cherish. In the minds of ordinary Christians – and Jews – the Koran teaches savagery and warfare, while the Bible offers a message of love, forgiveness, and charity…

But in terms of ordering violence and bloodshed, any simplistic claim about the superiority of the Bible to the Koran would be wildly wrong. In fact, the Bible overflows with “texts of terror,” to borrow a phrase coined by the American theologian Phyllis Trible. The Bible contains far more verses praising or urging bloodshed than does the Koran, and biblical violence is often far more extreme, and marked by more indiscriminate savagery. The Koran often urges believers to fight, yet it also commands that enemies be shown mercy when they surrender. Some frightful portions of the Bible, by contrast, go much further in ordering the total extermination of enemies, of whole families and races – of men, women, and children, and even their livestock, with no quarter granted.

I have extensively (and painfully) elaborated on this point earlier in this article series.

The comparisons between Muhammad “the warrior prophet” and Jesus “the pacifist” are equally faulty. For one thing, many were the “warrior prophets” in the Judeo-Christian tradition before Muhammad, including Moses, Joshua, Samson, David, Saul, and so many others. Moses, the prototypical “warrior prophet”, was the key figure of Judaism–would these Islamophobes vilify Judaism as they do Islam? (Nowadays it is often considered socially taboo to criticize Judaism but completely acceptable to malign Islam. Why the double standard?)

For the record, these Biblical prophets and holy figures are just as much a part of Christianity as they are Judaism. Christian theology holds these personalities in very high regard. Therefore, to suddenly limit the discussion to Jesus alone is misleading. Yet, this disingenuous tactic is critical to the Islamophobic rhetoric. If Islam is to be deemed a violent faith based on the personality of Muhammad, then both Judaism and Christianity must similarly be designated as violent faiths based on the personalities of Moses, Joshua, and all the other myriad of figures in the Bible who engaged in acts of violence far more atrocious than anything Muhammad stands accused of.

Leaving aside this point, it ought to be noted that Jesus as a pacifist is pure fiction. Prof. Reza Aslan recently published a book on Jesus, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, which disproves the myth of the pacifist Jesus. Although Aslan’s message may be news to some lay persons, it is in fact (as Reza Aslan himself points out) “old news” in scholarly circles. Thanks to the viral Fox News interview and Aslan’s addictive writing style, Zealot became a best-seller. Christian Islamophobes wrongfully assumed, without reading the book, that Aslan was attacking the character of Jesus. In fact, however, Aslan reveres Jesus, even while he dispels many of the myths about the man.

One of the myths that Aslan dispels is the idea that Jesus was a pacifist. Many Christians think of Jesus separately from the personalities of the Old Testament. But, in fact, there is a great deal of continuity in the Biblical narrative. According to the Bible, God rescued Moses and his people from Egypt and promised them the land of Canaan. However, Canaan was occupied by pagans, so God commanded the Jews to completely annihilate the indigenous population. This divinely sanctioned genocide helped establish a Jewish kingdom in the Promised Land. After some time, however, the Jews were conquered by outside forces. By the time of Jesus, the Jews were under imperial occupation by Rome.

What many Christians (and others) fail to realize was that Jesus was a Jew. He was in fact one of many different Jews who claimed to be the Messiah. The Messiah, it was believed, would be a conquering king sent down to liberate the Jewish people, “fight Hashem’s [God’s] wars” (Maimonides in Mishneh Torah, Laws of Kings 11:4), and then not only conquer but punish (with great vengeance) the enemies of Israel. Jesus’s connection to the war heroes of the Bible is underscored by the fact that he is called “a Davidic king”–the same David who engaged in acts of war and genocide against the Philistines and Amalekites. Aslan writes:

[A] fair consensus about who the messiah is supposed to be and what the messiah is supposed to do: he is the descendant of King David; he comes to restore Israel, to free the Jews from the yoke of occupation, and to establish God’s rule in Jerusalem. To call Jesus the messiah, therefore, is to place him inexorably upon a path–already well trodden by a host of failed messiahs who came before him–toward conflict, revolution, and war against the prevailing powers.

This was the role Jesus was claiming for himself by saying he was the Messiah. This is why the Romans crucified him.

In his book, Reza Aslan writes:

It was a direct commandment from a jealous God who tolerated no foreign presence in the land he had set aside for his chosen people. That is why, when the Jews first came to this land a thousand years earlier, God had decreed that they massacre every man, woman, and child they encountered, that they slaughter every ox, goat, and sheep they came across, that they burn every farm, every field, every crop, every living thing without exception so as to ensure that the land would belong solely to those who worshiped this one God and no other…

It was, the Bible claims, only after the Jewish armies had “utterly destroyed all that breathed”…only after every single inhabitant of this land was eradicated, “as the Lord God of Israel had commanded” (Joshua 10:28-42)–that the Jews were allowed to settle here.

And yet, a thousand years later, this same tribe that had shed so much blood to cleanse the Promised Land of every foreign element so as to rule it in the name of its God now found itself laboring under the boot of an imperial pagan power, forced to share the holy city with Gauls, Spaniards, Romans, Greeks, and Syrians–all of them foreigners, all of them heathens–obligated by law to make sacrifices in God’s own temple on behalf of a Roman idolater who lived more than a thousand kilometers away.

How would the heroes of old respond such humiliation and degradation? What would Joshua or Aaron or Phineas or Samuel do to the unbelievers who had defiled the land set aside by God for his chosen people?

They would drown the land in blood. They would smash the heads of the heathens and the gentiles, burn their idols to the ground, slaughter their wives and their children. They would slay the idolaters and bathe their feet in the blood of their enemies, just as the Lord commanded. They would call upon the God of Israel to burst forth from the heavens in his war chariot, to trample upon the sinful nations and to make the mountains writhe at this fury.

Jesus was crucified by the Romans before he could mete out vengeance on the enemies of Israel, but–as a I detail in my earlier article Jesus Loves His Enemies…and Then Kills Them All–he will fulfill this task during his Second Coming:

Jesus will “will release the fierce wrath of God” (19:15) on them, and “he shall execute the severest judgment on the opposers of his truth”. Because of this, “every tribe on earth will mourn because of him” (Rev. 1:7), and they will “express the inward terror and horror of their minds, at his appearing; they will fear his resentment”. Just as the people of Canaan were terrified by the Israelite war machine, so too would the unbelievers “look with trembling upon [Jesus]”. This is repeated in the Gospels, that “the Son of man will appear in the sky, and all the nations of the earth will mourn” (Matthew 24:30). “All the nations of the world shall wail when he comes to judgment” and the enemies of Jesus “shall mourn at the great calamities coming upon them”.

Far from the meek prophet of the First Coming, Jesus on his return will command a very strong military force that will “destroy[] every ruler, authority, and power”. Not only is this consistent with the legacy of conquests by the Biblical prophets, it is actually a fulfillment or completion of the task that Moses initiated: holy war and conquest in the name of God. In First Corinthians (part of the New Testament) it is prophesied that instead of loving his enemies, Christ will subdue and humble them under his feet:

1 Corinthians 15:24 [Jesus] will turn the Kingdom over to God the Father, having destroyed every ruler and authority and power.

15:25 For Christ must reign until he humbles all his enemies beneath his feet.

Reza Aslan concludes:

[T]he Jesus that emerges…[is] a zealous revolutionary swept up, as all Jews of the era were, in the religious and political turmoil of first-century Palestine–[which] bears little resemblance to the image of the gentle shepherd cultivated by the early Christian community.

Once Jesus is understood as a continuation and culmination of the Biblical narrative, it becomes clear that he was not a pacifist. The Biblical war ethic that Jesus believed in was arguably more violent than the equivalent Koranic discourse Muhammad operated from. (More on this in a future article.) The only difference was that Jesus’s rebellion was cut short by his crucifixion, whereas Muhammad triumphed against his former tormentors.

It should be noted that Jesus, like Moses and Muhammad, was an enigmatic personality; nobody can know for certain who the real Jesus was. People (including scholars) subconsciously project into Jesus their own self-image. Remembering Jesus as a pacifist is a healthy option for the Christian believer, especially when it forms the basis of a peace-loving theology. But, once that pacifist image is used by right-wing warmongers as a stick to bash Muslims over the head with, it’s time to call foul.

Danios was the Brass Crescent Award Honorary Mention for Best Writer in 2010 and the Brass Crescent Award Winner for Best Writer in 2011.